The Sordid Story of Paul Manafort

Volume 5, Character 1: Profiles of key players from the counterintelligence investigation of Russian activities in 2016 expose the Kremlin’s tactics

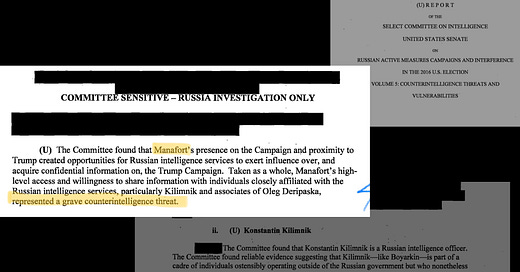

“Manafort had direct access to Trump and his Campaign’s senior officials, strategies, and information.”

“Manafort’s influence work for Deripaska was, in effect, influence work for the Russian government…”

“Manafort sought to secretly share internal Campaign information with Kilimnik.”

“Kiliminik is a Russian intelligence officer”.

- Final volume of the Senate Select Intelligence Committee’s bipartisan report on Russian interference in the 2016 elections

The American mind does not take well to the discipline of counterintelligence. The type of thinking required of counterintelligence specialists rubs the wrong way, and forces us to go against many norms cherished by Western society.

Just think of what your parents told you as a kid. If you can’t say anything nice, don’t say anything at all. People who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones. Everybody makes mistakes, and everyone deserves a break. In the counterintelligence world, you have to start by imagining the worst in everyone — not just in your enemies (not too much of a stretch), but also in your closest colleagues. This does not come naturally to most Americans. Part of our ethos is to believe the best in everyone, or that anyone can be better than they are.

Like many former and current intelligence officers, I have a healthy skepticism of politicians — not, as might be expected, from dealing with American politicians, but from having interacted with many of the foreign variety. And yet the two share many of the same character traits. Most of them believe they are the smartest people in the room. Most believe they understand the world better than the common man, and are therefore subject to different rules. Their staffs are usually worse, playing to the egos of their bosses, biding their time until they get their big break and move up the ladder.

Paul Manafort somehow represents the worst of all worlds. He started his professional life as a functionary in American politics, but then took his show on the road — mostly to the countries of the former Soviet Union, where corruption was rampant, and where presidents and prime ministers really did live by their own rules. He became a big fish in a small post-Soviet pond. In that role, where he was the American consultant behind the throne, Manafort was shielded from legalities, and from local or international scrutiny. Not surprisingly, when working with men like Ukrainian strongman Viktor Yanukovych, Manafort did well, and was paid a kingly fee. He learned to absorb, launder, and spend this money in the manner expected of a close confidant of oligarchs. By all accounts, it was clear that he enjoyed the lifestyle this afforded him.

Initially, it went swimmingly. But his story takes a sorry turn that lands him as a central character in all of the investigations into Russian activities targeting the US elections in 2016. When he took a plea deal to avoid trial for his activities as an illegal foreign agent and related financial crimes, he avoided having the true details of his connections to Russia explored in public.

But now all of this detail is exposed in the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s fifth section of its investigation into Russian activities surrounding the 2016 election. After reading its 996 pages, there simply is no believable narrative of innocence that explains Paul Manafort’s actions while associated with the Trump campaign. Manafort was a walking counterintelligence nightmare. There was no good reason to have someone so exposed to foreign influence in such a key position in the campaign, and his decision to pursue this position was entirely intertwined with those foreign interests.

Examining who Paul Manafort is, how he acted, and what he knew from a counterintelligence perspective will help to fully explain how firmly linked to Moscow his actions were.

* * * * *

I spent the majority of my 30-year career at the Central Intelligence Agency overseas, mostly in countries that could not in all honesty be described as Jeffersonian democracies. In fact, serving as a case officer — which is how we describe the men and women of the CIA who clandestinely recruit and run foreign spies in order to obtain their countries’ secrets, and in order to provide those secrets to US policymakers — those far-flung locations were part of the allure. There was always a healthy sense of competition in the CIA’s Clandestine Service, similar perhaps to that found between professional football teams — everyone is playing in the same league, but conscious of the performance of their individual team. Case officers serving in, say, Central Asia would often gently mock their colleagues serving in cushy European assignments. Ribbing along the lines of, “So, you got that intel report over coffee in a nice outdoor cafe? Tough assignment you got there. You should come out to my stomping grounds sometime if you want to do real spy work…” was common.

I personally wanted to live and work in the weirdest places possible. That’s where you have the most interesting experiences, where the best stories come from. Hell, anybody can get on a plane and after an overnight flight be sipping wine and eating cheese in Paris (at least, before COVID-19 changed all that.) I always thought that operating in Europe must be sort of like working at the bank — not the most scintillating job, but you left at 6 and brought home a paycheck, and they have some good museums to visit on the weekend. Serving in “The Developing World” — what our President Donald Trump refers to as “shithole countries” — was like working full-time on a safari. Beautiful undeveloped landscapes, loads of adrenalin, and a bit of danger mixed in. A cast of amazing, larger-than-life people — including the local intelligence services, as well as the characters from foreign governments involved in security and intelligence work. Everyone had a story.

This work with our foreign peers was often referred to as “doing liaison.” Collaborating with foreign intelligence services in countries that were trying hard to overcome their authoritarian histories (that includes almost anywhere in what used to be called the Warsaw Pact) was rewarding in its own right. Many of the foreign liaison officers I met and collaborated with had spent years in tuberculosis-ridden jail cells, where their not-Jeffersonian predecessors had left them to languish due to their opposition to the authoritarians in power. You could tell it still felt odd for them to be sitting behind the desk of a former mortal enemy who had been swept away after the fall of the Soviet Union. It must have been even stranger to be meeting with a CIA officer like me, after all those years of having been told that the CIA was evil and responsible for everything from attempted assassinations of Castro to the spreading of the AIDS virus. Additionally, these men (and in a very few cases, women) were struggling with the moral quandary of having essentially unrestricted powers — most answered directly to their presidents or prime ministers, and few of these newborn democracies had any sort of government oversight — but were trying to use their dark powers for good.

It would of course be naïve to say that all of them were acting only altruistically in the interests of their countries, but you’d be surprised how often they actually were. And many of them were aware of a unique aspect of running espionage services inside democracies: often it was a one-time shot, not a lifetime appointment like their Communist predecessors had. An intel chief in these new democracies often had to flee the country or go into hiding after he left the job, because inevitably the opposition party that won the election would accuse him of having spied on them. (Sounds familiar, no?)

I met dozens of versions of Paul Manafort during my work overseas. One thing many Americans don’t fully appreciate about the CIA is how wide a berth we give our countrymen when we encounter them abroad. Our job is to have as many foreign contacts as possible, but more than a casual encounter with an American was considered a waste of time. After all, they rarely have access to the secrets of the country they’re in, so why bother? And then there was all the paperwork, the waiver requests, the special requirements — and of course, the derision of one’s colleagues: “Oh, you met with an American? That’s so cute. Don’t bother to put in for overtime.”

Occasionally, you’d run into an American overseas who had spent significant time in the country, and had regular contact with people — foreigners — in whom you actually did have an interest. Often times, these Americans were retired overseas from government service, or were former businessmen who knew where the bodies were buried (usually, but not always, figuratively). Sometimes they worked for non-governmental organizations (NGOs), or were contractors for various international organizations. They were occasionally interesting to chat with at an Embassy reception, or over a beer at a local bar. But it was the exception to the rule that we viewed these contacts as worthwhile.

But foreign governments took a great interest in these various versions of Paul Manafort, who positioned themselves as connected players with dark arts of their own. What made such people attractive to newly-democratized governments in former authoritarian countries was that they were Americans, and they carried with them that special sauce which was American democracy. Countries trying to develop their own versions of the shining city on the hill were interested in folks who had experience in American politics. There were also the governments who wanted to try to convince Western diplomats that they would become more democratic, but actually had no intention of doing so — which was the case with Manafort’s best-known client, Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych.

Somebody like Manafort willing to work for this latter type could sell himself to an autocratic dictator controlled by Moscow (which accurately describes Yanukovych) as an expert image reinventor, somebody who could remake an autocrat hidden within the guise of a new, reforming post-Soviet society. It’s always nice to have an American telling you how to manage those pesky opposition groups… in a sort of pseudo-democratic fashion, or at least in a way that hopefully won’t run you afoul of the US and the West, whose wealth and markets you need access to, and whose good favor you may need to manage those pressures from Moscow.

* * * * *

When questioned about the precise nature of his work in Kyiv, Manafort claimed (with a straight face!) that he was working with Yanukovych to make him a more democratic leader. What he actually meant by this was he was exerting himself to make Yanukovych appear, to the casual observer, as more democratic. Manafort knew Yanukovych would never be a Ukrainian Thomas Jefferson — but he was being paid handsomely, so why not?

American intelligence officers understood that Manafort and his ilk, due to their consulting relationships with new authoritarians like Yanukovych, knew who was going to sell out whom, who was actually spying for the opposition party, or perhaps even spying for a neighboring country. This was the kind of information that would leak out over long lunches or dinners, lubricated liberally with wine or distilled spirits, or afternoons in the sauna with foreign despots. The Manaforts of the world began to develop a feel for who had a hidden agenda, or a concealed allegiance.

This feel, usually developed after spending considerable time in the country in question, actually provided them with what CIA officers thought of as “a counterintelligence sense.” Anyone with those kinds of contacts and some time on the ground would have at least the beginnings of that CI radar. A lot of this was about self-preservation. After all, if they were going to make the kind of money Manafort made — and those large sums were not uncommon in countries where the rule of law and independent judiciaries were still at the kindergarten level — they needed to know if somebody was out to screw them. They needed to know when and how that might happen. And of course, in the countries which once made up the Soviet Union and its puppet states, Russia always loomed large in this respect. If you were an American diplomat, spy, contractor, or consultant, you knew the Russians would be watching you. Because of course Vladimir Putin was worried that what you were up to was not diplomacy, or business, or consulting, but rather planning for regime change in Moscow.

So when I read that Paul Manafort claimed he had no idea that a Russian with good English who he met in Ukraine by the name of Konstantin Kilimnik might possibly have connections to Russian intelligence, I enjoyed a hearty laugh. For starters, if you received good English language from the Russian government (Kilimnik claimed to have studied it while in the military), you were almost certainly going to have intelligence responsibilities. (Russian diplomats were an exception to this rule, but it’s a distinction without a difference, because Russian diplomats essentially have no choice but to cooperate with Russian intelligence abroad when asked. The Russians call this “coopting.”) Second, given that Manafort was working for and spending lots of time with Yanukovych, he would have known who was who in Kyiv. Manafort’s blithe remark to the effect that “nobody was wearing badges” and therefore there was no way for him to identify a Russian intelligence officer might have placated Washington-based investigators, but for those of us who had already been on the safari for a while, it was a ludicrous claim. Of course Manafort would have known.

This denial about Kilimnik was not as vapid as it seemed. For there is another fact of life if, like Manafort, you were living large and working for a guy like Yanukovych. Such work, especially by an American, would have set off low-level seismic waves in Kyiv that would have registered on some very sophisticated equipment back in Moscow. Yanukovych and his security services would have run their own background checks on Manafort, to include checking with the much more powerful and better-resourced Russian intelligence services. It is inconceivable that Manafort, with all of his connections and his past, would not have known and understood what this meant. It meant he was on Vladimir Putin’s radar screen.

In addition to Yanukovych’s tight relationship with Moscow and all the reporting that would have accompanied this, Putin and his minions could also keep track of Manafort via the ever-discreet Mr. Kilimnik. The recently released fifth portion of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s (SSCI’s) Russian investigation (which is remarkable in its bi-partisan nature) confirmed that Kilimnik was a Russian intelligence officer. Whether Kilimnik was still on “active duty” for Russia while he worked for Manafort scarcely matters: like much else in Russia, when Putin picks up the phone and directs his people to request cooperation from Kilimnik, Kilimnik would immediately understand the dynamic. If he was unwise enough to decline, Putin’s next call would be to his security services to find out where Kilimnik’s wife and kids lived. Or his grandma and grandpa. Or what bank he kept his worldly savings in. And as it turns out, Kilimnik would serve as a valuable communications channel between Manafort and the Kremlin. Actually, as a technical matter, the communications channel would be between Manafort and a well-known Russian oligarch: Oleg Deripaska.

* * * * *

A brief aside on Russian oligarchs, whose role is sometimes misunderstood in the West. While they are well-connected, wealthy Russian businessmen, none of those descriptors carries the normal Western definition. Modern Russian oligarchs more closely resemble the boyars of tenth-century Russia. The boyars had arrangements with the tsars: they would be allowed to own huge tracts of land and become wealthy on the backs of peasants in return for allegiance to the Tsar. Allegiance meant that when the Tsar wanted to go to war, the boyars would provide troops and weapons and horses to make it happen.

For an example of how this system works in Putin’s 21st-century Russia, fast-forward to the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics. Sochi was a critical moment for Putin, who wanted very badly to show the world that Russia had emerged from the chrysalis of its gray Soviet past, had evolved into something new and sparkling. But this would be an expensive endeavor — so Putin began to canvass his oligarchs. “Igor, how’s that oil and gas monopoly I gifted you? Good, good. Listen, I need you to build me two stadiums and a skating rink in Sochi….” “Vladimir, are those railroads I gave you still running on time? Yes? Great! Get on the next one to Sochi, I need you to build a complex of hotels for the Olympics… no, no, not just one – probably at least four.” In short, oligarchs are part and parcel of the Kremlin’s work. And if you are an oligarch who challenges Putin, as Mikhail Khodorkovsky did in 2003, you end up spending a decade in a Russian jail and then being exiled — if you are lucky enough to avoid being killed. Everyone knows how the game is played. They built the stadiums and ice rinks, the hotels and the parks. They accomplish other tasks for the Kremlin when asked. Their wealth comes from that allegiance, just like the boyars.

Numerous excellent books can walk you through the cutthroat period of Russian history when the oligarchs got their start. The ‘90s were one of the few times when Russia actually had a brief but meaningful shot at joining the community of nations as something resembling a new democracy. Instead, the country turned to massive corruption. When Putin took the reins, it was game over. Corruption and authoritarianism were to be the lingua franca in Russia for decades.

Some oligarchs are beginning to show their age after these decades — but Oleg Deripaska still exhibits great energy. Many oligarchs are publicly reserved, but Deripaska has always played the game differently — which hasn’t always worked out for him. He is an interesting character. Young Oleg decided early on that he was going to be an oligarch. He started looking into Russian metals, specifically aluminum, and when he hooked up with Roman Abramovich as a business associate in 1994, he crossed the gem-encrusted threshold into the rarified air of full oligarchy.

From what little we know of the murky inside world of Russian oligarchs, Deripaska has a complex relationship with Putin. The two are undoubtedly close (or as close as anyone can be to Putin), but it is difficult to discern whether there is anything resembling a personal relationship, or whether it is all business. One interesting inflection point in the relationship — closer to a scene from the popular HBO drama “Succession” than real life — was when Putin visited a factory owned by Deripaska where workers had been protesting over not being paid. In a televised meeting with the factory leadership, prominently including Deripaska, Putin chose to humiliate Deripaska by criticizing his running of the plant. Towards the end of the meeting, Putin called Oleg forward like a schoolboy and forced him to sign an agreement to restart work and pay the employees. Deripaska hung his head and took his medicine, meekly signing as Putin looked on… but was it all for show? Why were TV cameras present? The incident, pre-planned or not, proved to be only a speedbump in Deripaska’s oligarchical journey.

Today, Deripaska is still widely viewed as close to Putin. Another thing which would not have escaped a guy like Paul Manafort.

Let’s review: Paul Manafort worked for Ukrainian president and Kremlin puppet Viktor Yanukovych. Manafort employed a Russian intelligence officer, Konstantin Kilimnik, in his consulting firm, and used him extensively in Kyiv. Back in Moscow, Vladimir Putin must have been aware of Manafort’s activities in Ukraine and beyond, due to his contacts with Yanukovych, and because Kilimnik was reporting back to Moscow. And lastly, since the mid-2000s, Manafort had known and worked with Russian oligarch Deripaska, who enjoys close access to Putin — and who does what he is asked when he is tasked by Putin.

If you know anything about how this part of the world functions — the bones of the Soviet security architecture that have been frankensteined into modern forms — all of this is quite straightforward.

* * * * *

Imagine for a moment that it is 2016 and you have been hired as a security consultant for the campaign of Donald J. Trump. Imagine further that an important part of your job was to ensure that anyone hired by the campaign would not have ties that would damage the candidate somewhere down the road. This would be especially true for senior members of the Trump team, such as the campaign manager. It would be reasonable to assume you would understand that someone like Paul Manafort — with all of his consulting overseas, his high-profile work for African dictators, and especially his close working relationship with foreign leaders with ties to Moscow — could be a problem from both a reputation and security perspective. No way would you want Manafort anywhere close to a leadership job — of course not. Common sense.

And yet, for some reason, nobody caught it. Nobody said hey wait, is it really a good idea for somebody like Manafort to be campaign chairman? It would have been a gross error on the part of any campaign security person not to at least inform campaign leadership that keeping Manafort would be a grave mistake.

Manafort was a walking counterintelligence nightmare. Prior to becoming Trump’s campaign chairman, Manafort made tremendous amounts of money traveling widely to places riddled with corruption. Furthermore, he worked directly for a group of thoroughly unsavory characters, first among them Viktor Yanukovych. And then, for the trifecta, in addition to all the corruption and contact with corrupt leaders, his preferred overseas workplaces were countries antithetical to US democracy as we once knew it — places like Ukraine, former Soviet republics in Central Asia, and the heart of darkness itself, Moscow.

If I were still in my old job at CIA, and an HR person came in and pitched me to hire somebody with Manafort’s precise resume and background, I’d have thrown them out of my office. Nobody with even a modest understanding of security and counterintelligence — hell, even with an ounce of common sense — would ever hire somebody like Manafort and then give him access to the kind of sensitive information to which a presidential campaign has access.

Unless the campaign simply didn’t care.

What kind of impact can someone with Manafort’s background have as a campaign manager? Well, let’s start with the party platform, which is typically finalized during a party’s convention. In 2016, at the Republican National Convention, Manafort was in charge. Perhaps taking his cue either directly from then-candidate Trump, or perhaps simply taking note of Trump’s past statements regarding Russia (such hits as “The people of Crimea… would rather be with Russia”; “NATO is obsolete”; “I think we can have a great relationship with Russia”; “Putin was my stablemate”), it seems Manafort began to add or modify planks in the Republican Party platform that favored Russia. In the counterintelligence and security world, that’s called a “flag” — behavior that is questionable and needs further investigation. Some inside the campaign raised the issue, noting correctly that under normal circumstances, Republican platforms did not support Russian geopolitical goals. In fact, usually the opposite.

But we now know that Manafort did much more than alter the party platform in favor of Russia. He actually reached out to his old friend and colleague (and as it turns out, Russian intelligence officer) Konstantin Kilimnik, offering him sensitive information from inside the campaign of the Republican nominee for President. And he went a step further: Manafort asked Kilimnik to talk to their mutual friend, Oleg Deripaska, and offer up a briefing by Manafort himself on what was going on inside the Trump campaign and inside the Republican party.

To be clear: what Manafort did was tantamount to offering up intelligence on the US political landscape to none other than Vladimir Putin.

It would go like this: Manafort talks to Kilimnik, Kilimnik talks to Deripaska and his people, Manafort passes inside information from the Trump campaign to Deripaska, and Deripaska briefs Putin. Manafort knew this is how it worked — he knew that information had more value if it made it all the way up this chain. He had used this channel this way in the past. It is still not entirely clear what information Manafort shared with Kilimnik, or if Kilimnik ever formally briefed Deripaska — but the path for that information to flow through was certainly there. And there can be no doubt whatsoever that Putin would have been very interested in such information.

And paths like that run both ways. Deripaska could have easily communicated with Manafort about, well, almost anything. He could have asked for more detail on Candidate Trump’s plans and intentions vis a vis Russia. He also could have asked Manafort to change or add planks in the Republican platform (this is what is referred to among intelligence officers as acting as an “agent of influence”). This is the kind of operation the Russian intelligence services could normally only dream of. But Manafort helped their dreams to come true. Manafort fought to gain this position in the campaign explicitly to rekindle his channels with Moscow.

When confronted with these facts, some point out that Manafort’s reason for offering up the “inside the campaign” briefings to the spy Kilimnik and the oligarch Deripaska was financial. Manafort was not a traitor, they say, he just needed some money. There was talk from Manafort of financially being “made whole” with Deripaska, as a result of the access to inside information he had in his position as Trump campaign manager.

From a counterintelligence perspective, such an explanation makes things not better, but much worse. There had long been financial difficulties between Manafort and Deripaska, and the oligarch claimed Manafort owed him significant sums. Deripaska had even sued Manafort, saying Manafort had gone into hiding to avoid answering questions about what had happened to investment funds he was supposed to be managing. The pressure Manafort must have been under — after his nearly decade-long cash cow Yanukovych, who paid him tens of millions of dollars, fled to Russia, and after he found himself in a deep hole with a man close to Putin — must have been tremendous. He didn’t see a way out. But now, Manafort could make it all go away by simply providing a briefing or two.

Manafort was a skilled and experienced player when it came to advising foreign officials on local politics, but his domestic political skills may have atrophied. He seemed to prefer political consulting for autocrats like Yanukovych in Ukraine, who weren’t really so concerned with running a clean or fair election — or perhaps this attraction to autocracy was one of the traits he admired in Donald Trump. Regardless, it was Manafort’s political consulting abroad that apparently finally did him in as campaign manager for Trump: too many in the American press were already raising questions that were difficult for Manafort to answer regarding his conduct in Ukraine and others in the former Soviet sphere. One particularly thorny issue was whether Manafort had ever registered as an agent of a foreign power with the US government, as required by US law, when he was lobbying Washington on behalf of Yanukovych, and hiring others to do the same. Only a month after the Republican National Convention in 2016, Manafort left the Trump campaign.

* * * * *

When he fell out with Deripaska, Manafort worked as hard as he could to get back into Moscow’s good graces, to the point of offering inside information on the Trump campaign — information for which any good intelligence officer would have paid handsomely. And indeed, given his finances at the time, it seems a good bet that that was precisely what Manafort was after.

When I was a manager at CIA, one of my most important jobs was to ensure that the operations for which I bore responsibility were as airtight and secure as they could be from a counterintelligence perspective. I can assure you that no competent American intelligence officer with counterintelligence responsibilities would have believed that Paul Manafort’s actions with regard to Russia were innocent.

This is heavily reflected in the pages of volume 5 of the SSCI report. The amount of detail on his activities and behavior simply leaves no believable narrative of innocence that explains Paul Manafort’s actions while associated with the Trump campaign.

Who in their right mind would have hired Manafort for any role in the Trump organization, with his record of accepting large sums of money from dictators, money and contacts he hoped to hide from US authorities? Who thought it was a good idea to hire the guy with connections to Moscow that ran both deep and wide, from his close working relationship with a Russian intelligence officer, to his suitor-like pursuit of a Russian oligarch with close ties to Putin? And why take those huge risks? Was Manafort really the only one who could fill the role as Trump’s campaign manager during the party convention? Nobody else would pick up the phone? Nobody else on the bench?

This gets back to the American discomfort with the mindset of counterintelligence. In the arcane world of counterintelligence, such rhetorical questions are quite useful. They force us to look beyond our common judgments, to resistour inclination to think well of people, as it is polite to do here in the West.

In the case of Paul Manafort, the answers to all the questions, rhetorical and otherwise, show what road Manafort was on. It was the one leading across the steppe to Moscow. And no one on the Trump campaign seemed to care.

— SH