The war on Venezuela is a war for American reality — PART 1

President Trump has pushed the nation toward a fulcrum — a point where the entire definition of American power could unhinge, and after which there is greatly increased risk for the United States of America. The possibility takes shape in the inexorability generated by the convergence of domestic narrative with events in the Caribbean. But it is sparked entirely by the way this American president wields power.

The justification for the military action in the Caribbean is based on a false narrative that is contradicted by our own intelligence. The threat we’re allegedly confronting isn’t any more real. The outcome we are being told to anticipate can’t be any more truthful. If this conflict is pursued, we will be left a weaker nation with closer relationships with our chief adversaries, having made choices that move us further from the nation that we think we are.

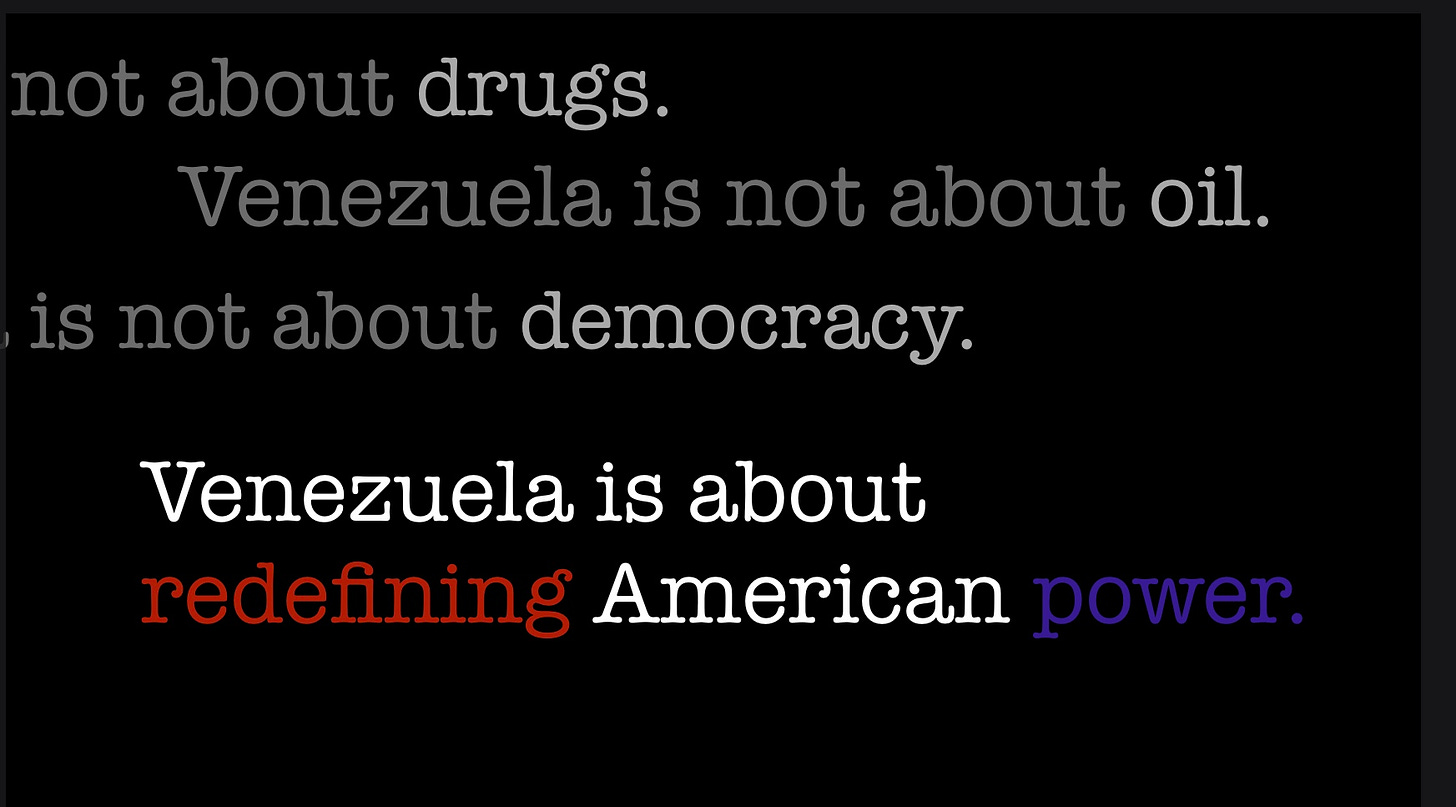

Venezuela is not about drugs. Venezuela is not about oil. Venezuela is not about democracy.

Venezuela is about redefining American power.

This Great Power long-read, which looks at the parallel lines of effort pushing us toward conflict with Venezuela, is split into 7 sections, posted as 2 parts [or subscribers can listen to the audio version here — https://www.greatpower.us/p/the-war-on-venezuela-is-a-war-for-1cc ]:

Part 1:

Introduction — All the president’s spiders

Narrative 1 — “Narco-terrorism”

Narrative 2 — Oil boom in Essequibo

Narrative 3 — Winning a “theater war”

Narrative 4 — “The only free hemisphere”

Narrative 5 — “Homeland” realignment

Conclusion — “Americas first” creates space for cooperation with Russia and China

PART ONE

Introduction — All the president’s spiders

Of all the problems I imagined having to solve in my adult life, one of them was not what to do when a regular household spider takes up residence in your nephew’s tarantula tank — a beloved pet which was left in your care after a move overseas. You weren’t exactly thrilled, but there’s a mutual nonaggression pact: you throw in some crickets and change the heat bulbs but otherwise leave it alone, and it eats the crickets and but otherwise wants nothing to do with you, either. Sometimes as it flings itself from the roof of the terrarium onto its prey, you appreciate that it is utterly terrifying and mesmerizing in form and substance — and that it is really quite mad that you have agreed to keep it captive in your house.

And now there’s this new conundrum: another spider is breeding in its tank. Maybe the new spider was too small for it to pay attention to, or maybe it even enjoys its company a little and thinks the tiny baby spiders are fun to watch. They fight over the tarantula’s scraps — and when there aren’t enough scraps to placate them all, they attack and suck each other dry. The baby spiders can still escape out of the screen at the top of the tank, but find that outside of the protection of the tarantula is great peril. Once the benevolence of the tarantula is enjoyed for too long — there is no escape. There is only life under the shadow of the tarantula, hoping to be big enough to eat other spiders but not so big that the tarantula decides it wants to eat them. The whole ecosystem can only survive because of the tarantula, with which you are trying to avoid a holistic confrontation but have nonetheless been feeding and making more terrifying.

Every time I make the daily cricket sacrifice to the spider, all I can see is the living allegory of the current US administration. The nation maintains a captive tarantula which has grown bored of containment and is seeking new entertainment. Gone are the men of the first administration who sought to constrain the president’s worst impulses and fend off the most damaging missives of favor-seekers. They’ve been replaced by men and women who share no ideology but collectively believe the president is the only horse they can ride to accomplish their ambitions, achieve their own personal salvation, or enable their own self-dealing.

The result is the proverbial “jar of spiders” dynamic amongst the cabinet and senior advisers — they know their only hope of survival is to outcompete (and often eat) the other spiders —but it’s layered under the Stalinesque patina of this particular president, who encourages the mortal competition between loyalists because it all makes for better ratings for the show.

From week to week, the contestants are up, down, in, out, clinging with bloodied fingernails, sitting on a gold-painted fake bamboo chair next to the president in his Florida resort property — a chair upon which no one sits with any particular comfort.

Understanding this unsettled, rickety, non-collaborative environment is key to grasping how it is that a significant percentage of America’s naval power has converged in the Caribbean toward the big red arrow pointing at Venezuela.

There are so many different interests seeking to influence the president on any given day — foreign, domestic, allied, adversarial, overt, covert, corporate, techbro, religious ideological, creepy ideological, a desperate few patriotic ideological — that they inevitably collide — but sometimes converge, generating unexpected momentum.

Few places has this dynamic been more observable than in the mobilization underway in Latin America. The separate interests seeking to escalate the conflict each have different reasons for doing so and present different justifications to spur the president forward. They aren’t collaborative, necessarily, but they share chaotic directionality — rocks rolling down a hill. The motion generates a sense of urgency, competition, inevitability. It may now be impossible to escape.

But that doesn’t make it real — any of it.

President Trump has pushed the nation toward a fulcrum — a point where the entire definition of American power could unhinge, and after which there is greatly increased risk for the United States of America.

The possibility takes shape from the inexorability generated from the convergence of domestic narrative with events in the Caribbean. But it is sparked entirely by this president’s vicious, lascivious manner of wielding power.

The cost for Americans will be high.

Events in the Caribbean deserve far greater attention

Four things are important about the departure point at which we have arrived.

First, the operations targeting “drug boats” are explicitly about creating a narrative that expands the permission structure for the use of the US military domestically. (There will be additional detail on this below, in the Narrative 1.) In the back and forth between the administration and lawmakers about the legal justification of these strikes, the truth of their impact is clear: they erode both the rules of war that guide and constrain our use of American hard power overseas and the rule of law that should govern how law enforcement can use force at home. This blurring of justification weakens both, exposes America to great and unnecessary risk, and will have significant impact on the lives of everyday Americans and American men and women in uniform.

Second, the movement of US hard power assets to the Caribbean is likely a first step toward the new national defense strategy (and accompanying global force posture review) being crafted by the Trump administration. In its current form, that strategy formalizes the domestic/foreign security fusion by prioritizing “defending the homeland” from largely narrativized threats above defending the nation from actual adversarial global threats from Russia and China. Around 11 percent of US naval assets have been moved to the Caribbean, with some 15,000 troops aboard, plus accompanying air support and shifted priorities for special operations and intelligence assets that have been retasked to prepare options for Venezuela. America’s top military commanders have been leapfrogging across the region. Never has Trinidad and Tobago been such an important official destination (though of course, no ambassador has been nominated for this post, so there is only a chargé).

Some of these deployments may be temporary or rotational — the whole point of Marine Expeditionary Units and aircraft carrier groups is, after all, that they can move to where they are needed. But a mothballed airbase in Puerto Rico has been reopened, US planes have been spotted at regional airfields, and a panoply of new defense cooperation arrangements have been discussed or agreed to with nations around the Caribbean basin (with the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Panama, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, and also with Ecuador, though the parliament voted down a proposal for a US military base, which would require a constitutional change; Grenada is still considering a US request for a radar installation). While the terms of the security discussions are not always public — and many relate to expanding intelligence and surveillance capabilities — they are mirrored by the White House’s aggressive announcement of frameworks for trade deals with these nations (removing tariffs and other incentives are the reward for agreeing to support US security operations in the region — and to accept deportees).

FOIAed documents have shown at least some sustainment preparations for expanded US military presence in the region through the end of the administration (2028). The administration has pushed ahead with the “Americas first” play despite knowing it undermines confidence with our traditional treaty allies and is costing us valuable intelligence sharing partnerships (reports cite the UK, the Netherlands, and France as having suspended intelligence sharing relating to operations in the Americas, as well as Colombia). The choice to pursue viral video attacks that many assess as akin to extrajudicial killings — layered with strange, grotesquely transactional behavior toward Russia — is slowly eroding the fabric of trust that necessarily underlays our most essential partnerships. Which it becomes clear is an end intentionally pursued by the means, and not an accident.

Third, a war on Venezuela will define a new vision for American power — maybe by happenstance, but a new vision nonetheless. Right now this vision is being presented by the administration as a display of newfound “toughness” in a time when “hard decisions” are needed. In reality, it is solidifying the diminishment — via the contraction — of American power. Rather than countering the global adversaries we know we face, the pursuit of the “Americas first” policy creates space for cooperation with those adversaries (this will be discussed in Narrative 5). It also elevates their methods and strategic perspectives above those we have defended, as the free world, since the end of WWII. Every time Trump does this, it’s a possibility no one was willing to consider. We should see this with clarity, for once.

Fourth, it is also no accident that we find ourselves speeding toward a culminating point in this definitional war, with pressure to move on the “Ukraine peace deal” and American action against Venezuela mounting in parallel. Talks with allies are deprioritized as attentions are divided. Stepping away leaves too much space for the other spiders to pounce.

It is, disconcertingly, Mr. Trump himself who seems the least convinced about escalating from drug-boat bullying to direct action in Venezuela. As per usual, he is enjoying how the threat of war works in the show — but the story arc of the actual war may require a commitment of too many episodes. “If we can save lives, if we can do things the easy way, that’s fine,” Mr. Trump said this week, in indicating he may be open to speaking to Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro. “And if we have to do it the hard way, that’s fine too.” Of course, it turned out Trump had already spoken to Maduro. By the end of the week he “declared Venezuelan airspace closed” — a thing he cannot do unless he means via military means, but the aircraft carrier had already arrived in-theater and was just sitting, and some sense of movement was needed to advance the plot. Twenty-four hours later, he said it didn’t mean anything. Apparently he had given Maduro an ultimatum to leave the country, and the window had expired.

Trump’s speeches and actions are disjointed and hardly rousing for the cause — any cause, even if you think the cause is playing hard to get on a “deal.”

But all around Trump are people who have decided that a crisis with Venezuela is the way to advance their cause. The cadence of crisis is beating, beating, beating — and both our adversaries and all the spiders in the jar are a part of the thrum. Everyone is so eager to get something they want out of the president — and believe this is more possible now than any time in history — that the convergence of purpose is whipping us ahead. But toward what, exactly, few of the drummers are overly concerned.

The array of justifications crafted for intervention in Venezuela indicates a much bigger conflict than anyone is imagining

The media discussion has focused primarily around questions of under what legal authority the military strikes against alleged “drug-boats” are being conducted. This discussion is incredibly important. But there is a far more complex series of internal discussions about potential justifications for removing Maduro from office or conducting military strikes within Venezuela.

These fall into several categories:

Narrative 1 — “Narco-terrorism”

Narrative 2 — Oil boom in Essequibo

Narrative 3 — Winning a “theater war”

Narrative 4 — “The only free hemisphere”

Narrative 5 — “Homeland” realignment

Each of these is discussed below.

Narrative 1 — “Narco-terrorism.”

Or, how the Maduro regime’s alleged support for cartels/drugs/immigrants/crime are direct threats to the lives of Americans.

Stephen Miller, whose own family immigrated to America in the last century, has earned his bones in the MAGA universe as a cartoonishly villainous pusher of anti-immigrant sentiment. Since 2015, right-world relied on stories of migrant workers and “immigrant criminals” to gin-up hatred of “the other” as a reason for America’s problems and declining sense of opportunity. During the first Trump administration, certain individual stories took on a totemic value within the broader narrative, and it all barreled ahead under the “build the wall” chant. Eventually, some of Trump’s closest advisors pleaded guilty of defrauding investors in a private wall-building scheme.

But the wall was a dead idea. The 2024 election cycle needed a juiced version of this story to escalate the sense of chaos — chaos that only a mega-disruptor like Trump could solve. Thus began “the invasion.” This narrative was the elevation of the threat of semi-controlled migration into an “invasion,” and then immigration was linked to crime, then gang violence, then drug trafficking. Eventually it became a story of immigrant gangs flooding America with drugs and dangerous migrants, killing and poisoning Americans. GOP electors happily waved “mass deportations now” signs at the convention. During the transition and early days of the new administration, the “invasion” became the argument for the use of military deployments domestically.

But if it’s an “invasion,” you need a foreign baddie. And that became Venezuela — because, basically, absolutely nobody likes Maduro (but more on this in the conclusion of the piece).

So, there was a narrative constructed to win an election and then drive internal action — to fuel mass deportations via wildly expansive enforcement activities operating with little oversight and $170 billion budget. But to sustain that narrative — and the swelling powers and slush funds — external action became required. The administration’s own intelligence assessment found little connection between Maduro, drug trafficking, and the cartels he supposedly directs — so they asked for it to be rewritten in a way that would better align with their narrative.

Now the domestic and foreign false narratives echo back and forth in a reflexive call-and-response — we are rounding up the “dangerous migrants” “bringing drugs” into America, and we are killing alleged drug-traffickers on the seas. The cacophony overwrites the fact that this narrative was only ever loosely connected to reality, at best.

This series of falsehoods and distorted truths is the entire public basis for military action in the Western hemisphere. The designation of drug-runners as “narco-terrorists” and of some of the gangs as foreign terrorist organizations is meant to convey some higher organizational purpose that allows them to be legitimate military targets. Military assets have convened to conduct flashy strikes — a vastly disproportional use of American hard power aimed at the lowest point of intervention in a trafficking hierarchy, traditionally dealt with as a law enforcement activity. Few outside hard MAGA loyalists seem convinced by the narco-terrorism label, nor by the inability of the administration to produce more information on who has been targeted in the boat strikes and why.

But the immigration/crime/gangs/drugs storytelling and the loose legal reasoning it provides have been a primary driver toward military action and underlay the Justice Department’s opinion that the boat strikes — but likely not strikes inside Venezuela — are lawful orders.

For Miller and his ilk, the point of the Caribbean operation is that it also escalates the sense of crisis that the internal security operations are meant to address — providing even greater cover for the expanded brutality and disregard for civil rights of immigrants and American citizens alike, and for the presence of the American military in American cities.

Narrative 2 — Oil boom in Essequibo

Overall, the idea that whatever is going on around Venezuela is “all about oil” is overdone. But, oil is kind of around all of it. It’s the grease on the gears, if you will.

One of the things rattling around the Pentagon is some kind of memo that connects potential military action against Maduro and Venezuela to an analysis of Essequibo, a territory which comprises roughly two-thirds of Guyana but which Venezuela has historically claimed based on some colonial shadowpuppetry or other. Following the discovery of large offshore oil reserves and other strategic resources in Essequibo, Maduro has been more actively engaged in interference in the territory, making claims on the land, holding elections for new leadership, sending Venezuelan ships to pester the oil fields.

It’s the last part, of course, that is the real problem, and the only reason you would hear the word “Essequibo” in the Pentagon. Because the biggest shareholder in the Essequibo oil project is ExxonMobil.

A quick step back here to flag one of those connections between negotiations over Ukraine and whatever is happening in the Caribbean — ExxonMobil. Exxon had been aggressively lobbying the White House/backchanneling with the Russians about re-establishing operations in Russia. This was discussed during the Alaska summit. Putin issued a decree allowing Exxon to re-enter the Russian market the same day. In September, Exxon signed an agreement with Rosneft to recoup almost $5 billion in losses that occurred after the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, when US companies had to exit the Russian market. It’s a nice sweetener for helping get improved US-Russian relations back on the menu.

It’s not that fanciful to believe that if Exxon is pushing the administration on Russia, it also has access on issues like Latin America where they have an easy story to tell to an oil-driven president. We’ve already seen signs of this connection. As President Trump stepped up sanctions on Russian oil and increased pressured on those still buying Russian oil and gas, he drew some praise for this tougher stance on Russia, even though it was just as likely this was about his overall obsession with US oil and gas production as anything to do with Moscow. In fact, when Trump pressured India to stop buying Russian oil, India replaced some of their Russian sources with oil from Guyana — a huge deal for Guyana and for Exxon. In August, Trinidad and Tobago also signed a deal with Exxon to develop deepwater oil assets, a deal which Exxon had been pursuing since before Trump’s re-election.

There’s one additional sign of Exxon’s clout in events around Venezuela. Chevron, another American oil major, has long been a primary investor in Venezuelan oil via a partnership with PDVSA (the Venezuelan oil company). Chevron has a complex relationship with the Venezuelan government, and in many respects has been a key lifeline of hard currency payments into the Venezuelan economy under Maduro. Chevron is only allowed to operate amidst all the sanctions with a special US license. The Trump administration suspended the license in February as part of its renewed pressure on Maduro.

But Chevron had been planning for its future. In July, it won a long legal battle with Exxon resulting from Chevron’s acquisition of Hess. Hess had been a stakeholder in the Guyana oil project, and Exxon and the other partner had unsuccessfully argued that they should have the right to acquire the Hess stake in the Stabroek block. With Chevron as Exxon’s new partner in Guyana, their license to operate in Venezuela was suddenly restored. (Under the revised license, hard currency payments are not allowed, so Chevron hands oil over to Venezuela, which it mostly sells to China, and now Venezuela survives on crypto exchange. Its crypto partner is Binance — the founder of which Trump recently pardoned in another self-dealing scheme. But those are rabbitholes for other days.)

So there are two American oil companies directly and indirectly connected in some way to Venezuela’s ability to survive as a petrostate. That already looks bad — especially with all that oil getting sold to China at discounted, desperation rates — but it’s standard fare for extractive industries.

But it is also necessary to factor in that a major partner of PDVSA is a renamed subsidiary of Rosneft — in fact they just signed a new 15 year agreement as one aspect of an expanded Russia-Venezuela strategic partnership agreement. PDVSA fundamentally relies on Chevron’s technological and engineering inputs to keep the Venezuelan oil industry alive, and Russia and China both benefit from this. Oh, and that third partner in the Stabroek block in Guyana, that was fighting with Exxon against the Chevron acquisition? That’s CNOOC, a Chinese state-owned oil company. Several Senators have asked Exxon to clarify its tax payments in relation to the Stabroek block, concerned that US taxpayer money may be de facto subsidizing the operations of a Chinese state oil company.

So you’ll pardon me when every time someone claims whatever is happening in the Caribbean is “countering Russian and Chinese influence” — well, it’s a nice talking point that can get right down off its high horse and wade around in the murky oil dealings with the rest of us. (But we’ll revisit this in Narrative 5.)

Back to Essequibo, the disputed territory in Guyana. The paper circulating describes Essequibo as run by a Venezuelan paramilitary group being run by the Venezuelan government, and it suggests the designation of this group as a terrorist organization. This would seem to be Cartel de los Soles, which the State Department recently designated as a foreign terrorist organization.

Cartel de los Soles isn’t really a cartel, it’s a name applied to an alleged network of corrupt and criminal dealings within the Venezuelan government itself. The State Department says Cartel de los Soles operates as an extension of the Venezuelan regime, with support from military and other officials. The US asserts this cartel supplies drugs to the US market and is thus a direct threat to its national security.

The State Department language on Cartel de los Soles is pretty loose: “The Cartel de los Soles is headed by Nicolás Maduro and other high-ranking individuals of the illegitimate Maduro regime who have corrupted Venezuela’s military, intelligence, legislature, and judiciary. Neither Maduro nor his cronies represent Venezuela’s legitimate government. Cartel de los Soles by and with other designated FTOs including Tren de Aragua and the Sinaloa Cartel are responsible for terrorist violence throughout our hemisphere as well as for trafficking drugs into the United States and Europe.”

Leaning on the Venezuelan government as illegitimate and drawing connections with red strings on a tack board is a slapdash way of declaring a foreign government to be a legitimate target of potential military operations that are supposedly targeting “narco-terrorists.” The Treasury designation links Cartel de los Soles to both Tren de Aragua and the Sinaloa Cartel — and by claiming Maduro is directing both groups against the United States, the “narco-terrorist” thing is supposed to take on a deeper meaning.

But the red strings represent shaky intelligence, at best. A declassified US National Intelligence Council report from April, which examined the Venezuelan government’s ties to Tren de Aragua, found that some regime members “may cooperate with TDA for financial gain,” but there is no evidence of systematic cooperation. “The Maduro regime probably does not have a policy of cooperating with TDA and is not directing TDA movement to and operations in the United States… [The NIC] has not observed the regime directing TDA, including to push migrants to the United States, which probably would require extensive coordination and funding between regime entities and TDA leaders… highly unlikely that TDA coordinates large volumes of human trafficking or migrant smuggling.” Mexico has also said there is no investigation of links between Maduro and the Sinaloa cartel.

A Trump appointee pressed for the assessment to be rewritten. DNI Gabbard fired intelligence officials responsible of the report in an effort to get the eye of Sauron off of her. In September, she recalled the report. By then, people were less interested in the migration/deportation explanations than the justification for the strikes in the Caribbean.

But elements of the Miller narrative had been told for so long, it would have been easy enough for Exxon to lean in. Exxon has been engaged in a years-long arbitration case against Venezuela over seized assets, which has not gone the way Exxon hoped. On March 1, a Venezuelan ship approached the Exxon/CNOOC fields off Guyana and made threats. In May, Venezuela held elections for new representation of Essequibo (in 2023, Maduro held a referendum to advance Venezuela’s historic claim over the territory, but it is not controlled by Venezuela). Venezuela has accused Exxon of conspiring to get Chevron operations in Venezuela suspended, and of financing Venezuelan opposition leader Maria Corina Machado as part of an effort to get the US to remove Maduro from office. Machado supported the suspension of Chevron’s license. In an interview for Donald Trump Jr’s podcast back in February, she said US oil companies will make a lot of money when she privatizes Venezuelan oil production.

Leaving aside any conspiracies — Maduro’s actions relating to Essequibo create an opening for additional justifications to act against him. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has been tracking developments in Essequibo, warning Venezuela to back off during his visit to Guyana in March. If Cartel de los Soles allegedly “controls” Essequibo and is in turn controlled by the Maduro regime, fighting the “narco-terrorists” tumbles into liberation narratives beyond Venezuela itself.

Essentially, you can say a territory “illegally occupied by Venezuelan proxies” must be restored to Guyana to make America safe. If you wanted to, anyway.

[… continued in part 2]